How ‘Uncle Cyril’ saved the world

Cyril Pustan was, to all intents and purposes, an ordinary working man, but his life story is nothing short of extraordinary. He took part in events which arguably helped shape the modern world, in particular our views on weapons of mass destruction. Cyril was part of the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace in 1961, had tea with Nina Krushchev, wife of then-Russian premier Nikita Krushchev, and he married Regina Wender Fischer, mother of chess grandmaster Bobby Fischer.

An avid diarist, his musings recall his experiences of living through the Blitz during the Second World War, of the Peace March, the building of the Berlin Wall, and the age-old struggle of the proletariat against the State.

Cyril’s nephew, Laurence Saffer, who is married to his niece, Sally, has brought his story to life in a book, Plumber, Lecturer, Pacifist, Spy (?), a biography replete with extracts from Cyril’s own diaries – the question mark relates to a speculation about part of Cyril’s life which is resolved in the book.

Speaking about the work, Laurence, from Leeds, said: “I heard many stories about Cyril and his adventures. He was the eldest brother of my wife’s mother. When she passed away, we inherited two boxes full of his writings. When I looked through them, I saw there was a story worth telling.

“We are all used to reading about famous people like Winston Churchill, Gandhi and Nelson Mandella, and the great societal changes they helped bring about, but the truth is it’s the ordinary folk who took part in these huge public demonstrations that made politicians sit up and take notice. Without them, we’d all be living in a completely different world. Each one of them, in their own way, helped save the world.”

He added: “It has been an honour to bring Cyril’s story to light, and I hope that in future, it might help enlighten a new audience, and give context to what were truly momentous times.”

Born in 1929 in London to Ukrainian immigrants, Cyril grew up in Shoreditch, London, the eldest of seven siblings. His teachers pegged him as “troublesome and untidy” but a “good worker”, traits that would arguably play out in later life. As a child, he lived through the Blitz – his diaries recall wandering the streets of London “past heaps of rubble [and] scattered debris, the smouldering ruins of buildings and houses” and “watching glowing embers of wood drifting on the breeze”.

His early political views were formed here, amid this “clash of ideologies”, set against a backdrop of broken cityscapes, disrupted education and constant fear of ‘the bomb’.

Cyril became a plumber’s mate but remained an avid diarist, dabbling in poetry. He found an outlet for his political views in the Communist Youth Association, although he later resigned through fear of being arrested – such was the political schism between East and West at the time. The Cold War began in 1947, polarising politics, while subsequent events such as the ‘space race’ and Cuban missile crisis in 1962 led only to further ideological entrenchment.

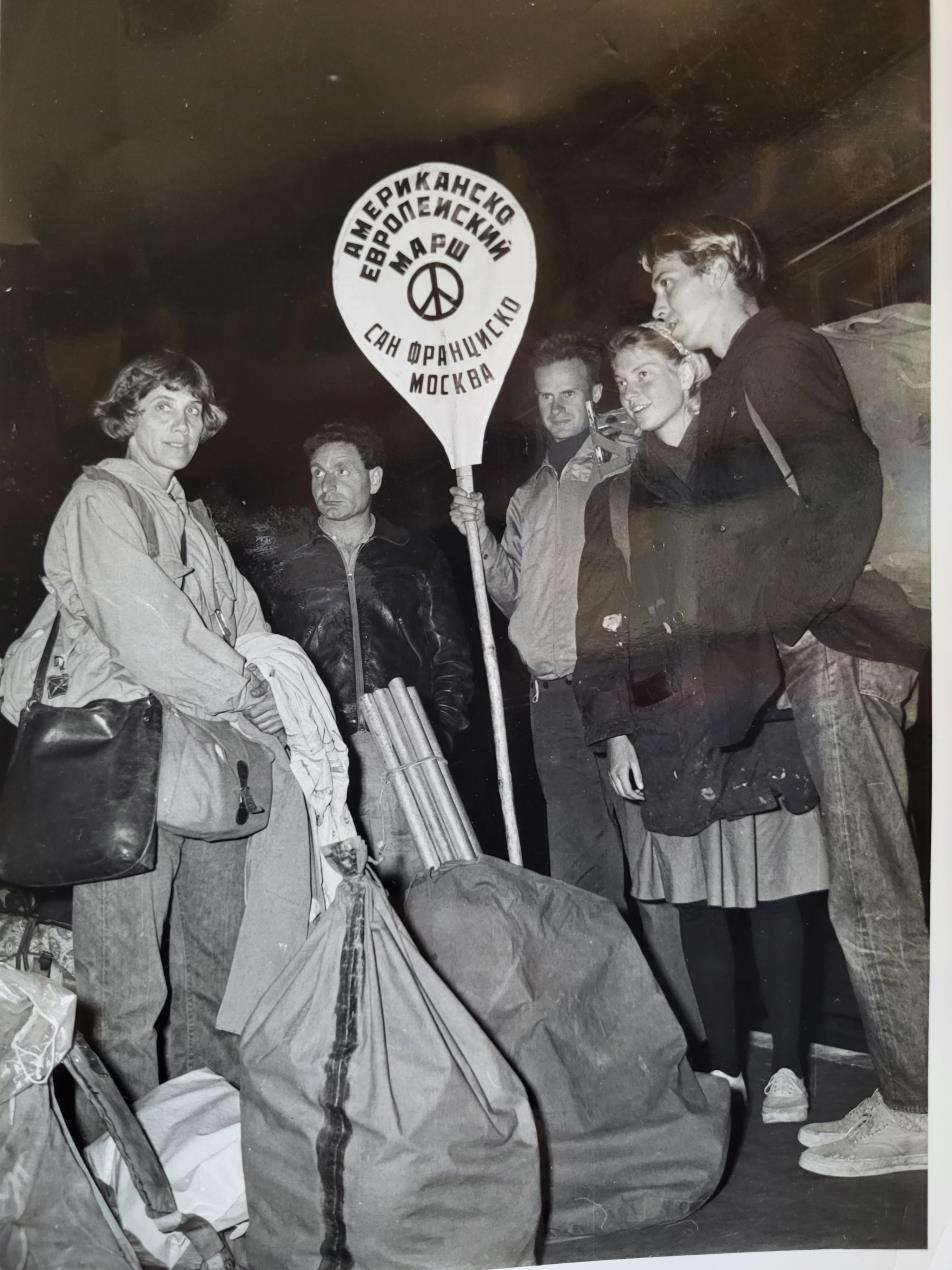

The Walk for Peace began as an earnest anti-war, anti-armament movement in San Francisco in November 1960 and ended in Red Square in October 1961. Cyril took part in the European leg and went on to Russia via France (where he and others were initially refused entry) and Germany. While attending a 5,000-strong rally in Trafalgar Square, his diary notes: “Standing high up on the plinth under Lord Nelson, we fight a losing battle with the pigeons calmly roosting above… We look out into a sea of faces and banners. It is a thrilling moment. For the first time we can see… there are many people who take us seriously.”

Cyril characterised the movement as one driven by “wartime experiences”, its agents “sincere partisans of peace” who would “no longer support the military politics of their country.”

The march drew thousands of supporters at various points along the way and ended with a formal dinner with Nina Khrushcheva, wife of Soviet leader Nikita. It also helped cement into the collective consciousness the idea that protest was not a forlorn hope. For Cyril, the march was also where he met his future wife, Regina Fischer, mother of chess prodigy Bobby. Cyril proposed to her on the train back from Moscow.

The couple eventually settled in Jena, a university town 165 miles south of Berlin. Cyril became a welder and recalls: “I remember the beginning – burnt fingers, cascades of sparks cunningly sneaking through buttoned clothes… Those days are forgotten. Now I lie uncomfortably comfortable, weld without conscious effort, and dream the dreams which a wandering mind can…”

His curious mind and lively disposition led to him landing a job as an English teacher at Humboldt University in 1963, where he taught both students and academics. He went on to gain a degree in English and wrote his thesis on the role of the English folk song in teaching foreign languages, later citing how many who had learned English and “forgotten practically every word” could nonetheless easily recall the words to ditties such as She’ll Be Coming round the Mountain.

In 1967, he even branched into film, landing a bit-part in The Frozen Lightening, as the Chief of Staff of the Royal Air Force. He later returned to the UK, studying a postgraduate diploma in phonetics at the University of Leeds. He died in September 1977, following a period of ill health.

In a diary entry to then-wife Regina in November 1972 (the couple divorced and Cyril remarried before his death), he wrote: “To work effectively, man must use his intelligence. The human frame alone, powerful as it is, is yet relatively uneconomical as a sole unit of power and work. One must use as levers for effectiveness mediums that appeal to intellect… Jail may get publicity, but if one’s efforts are not in keeping with general public feelings… one gets kicks from all sides.

“One must appeal to reason, not emotions. Mental violence and aggressiveness alienate, while reason attracts reasonable people and convinces them…”

Laurance, who has now offered Cyril’s writings to the JB Priestley Library, added: “When we inherited Cryil’s writings, and learned more about his life, I thought his story was worth telling. There is a passage in the Talmud (one of the central texts of Judiasm) that says if one person saves the life of another, it is as if they have saved the whole world. This is the story of the continuum of ordinary people who might otherwise seem to have nothing remarkable about them, but when you look at their journey, in this case Cyril’s journey, you realise that in some small way they have influenced the world we all live in today.”

The Cyril Pustan archive collection has recently been kindly donated to Special Collections at the University of Bradford’s JB Priestley Library and will be made available to researchers in the near future.

Plumber, Lecturer, Pacifist, Spy (?) is available on amazon.